The son of a Staten Island, N.Y., gas station mechanic, Chris Cosentino grew up knuckle-deep in a gear-driven life. When he was nine, his father said he could have a go-kart if he built one. So he did. By hand. Alone. And it worked.

The son of a Staten Island, N.Y., gas station mechanic, Chris Cosentino grew up knuckle-deep in a gear-driven life. When he was nine, his father said he could have a go-kart if he built one. So he did. By hand. Alone. And it worked.

The resolute young builder grew into a high-octane addict. He rode, wrenched and modified dirt bikes, muscle cars and street bikes throughout his youth. Cutting machines his own way was in his blood.

That genetic coding led Cosentino to become the lab partner of choice while at engineering school at Cooper University and, after he was out of school, to found a one-man engineering consulting firm that uses rapid-prototype machines and Cosentino’s fertile mind to build prototype parts of nearly any shape or kind.

Cosentino got heavily into sportbikes after college. He dabbled with vintage racing and moved on to race a Honda RS125. His natural tendency to build things his way led him to build his own race bike. His homegrown project steadily transformed from a Frankenbike weekend racer into a designed-from-scratch V4 race weapon.

The beginnings of Cosentino’s descent into midnight tuning were simple: He just wanted to ride.

His mechanical skills came into play with his first street bike, a powerful but notoriously poor-handling Kawasaki KZ1000. Not long after he bought it, he crashed hard; the machine was nearly a total loss. He tore the bike down and completely modified it with a new fork and custom-built swingarm. His hand-built additions improved the Kawasaki’s performance and his self-assurance.

“I had the confidence from having done all this stuff as a kid,” Cosentino says. “You realize that you can build something and, yeah, I’ll go ride it, and if I break my ass, I break my ass. If I don’t, I don’t.”

He moved up to a Yamaha R1 and met fellow motorcyclists Todd Puckett and Gregor Halenda shortly thereafter. The guys spent their weekends riding New York’s Bear Mountain region. They liked to ride hard and next decided the track was a safer place to do that. After a couple of track days got them hooked, they gave vintage racing a go, thinking it was a cheap way to get into the sport.

They soon discovered vintage racing is hardly cheap and moved to racing Honda RS125s. These light racers are fun to ride. They weigh in at about 150 pounds, which is less than half the weight of nearly any other motorcycle on the track.

“It felt like riding a little razor blade,” Cosentino says.

Racing the RS125 whetted his appetite for light racing motorcycles. He also wanted more of a challenge than just racing a production bike.

“I believed there had to be a better way,” Cosentino says, “and I believed I could find a better way because I’m a smart guy.”

As he looked deeper into how racing rules are structured, he saw that the only classes that would allow him to race his hand-built bikes were single-cylinder classes. So he put some time in designing a light, single-cylinder race bike.

Cosentino’s training is in computer-aided design (CAD), so he started sketching a chassis on the computer. CAD allows a lot of experimentation without requiring the designer to build test parts out of metal. After a couple of years of tinkering, Cosentino had a sophisticated, innovative chassis design.

Designing in CAD is so efficient, it can eventually become a limitation. “Some people just keep clicking on the computer,” Cosentino observes, “and some people walk into the shop and start building. So I walked into the shop and started building.”

His first prototype used an air-cooled Rotax single-cylinder engine. In October 2001, he debuted the bike at a Championship Cup Series race at Daytona.

The single-cylinder Rotax engine provided power and agility — but it was raw and utterly untested.

“The frame was still warm from welding as we were loading it into the trailer,” he remembers. “It really wasn’t quite ready yet but … I was going to take that bike and race it.”

After a very long and troublesome weekend trying to get it tuned properly, he managed to make his race and finished second-to-last in the Heavyweight Sportsman class. Just getting the bike running and limping it through the race was a victory of sorts, and he learned some hard lessons at Daytona.

The first was that building a race bike of your own design was possible, as he believed. Turning it into a functioning machine was a much more difficult challenge than he anticipated.

Once that was sorted out, the bike was reasonably fast and very strong in its class. More power was required to move up a class, and the Rotax air-cooled single could only stretch so far.

When a friend bought a scrapped Ducati 999 engine from eBay, a light went off in Cosentino’s head. The Ducati’s top end could provide the additional horsepower he wanted.

So he went to work designing all the parts necessary to graft the Desmoquattro top end to the Rotax bottom end. To make that work, Cosentino hand-fabricated so many parts that the result is a custom design, essentially.

The Cosentino custom is impressive on the track, running wheel-to-wheel with larger-displacement twin-cylinder machines such as highly modified Buell 1200s and Suzuki SV650s. The engine has been upgraded from a 999 to Ducati’s newer 1098 top end, with stellar horsepower output but dicey reliability.

As practical as he is analytical, Cosentino realized a few years ago that his riding skills were becoming the bike’s limiting factor. To stay at the front, he recruited his friend Todd Puckett to take the controls.

Cosentino has already gone from images on a screen to a class-dominating race bike. Yet he believes there’s even more speed and prowess in his design, which a third generation can bring to perfection.

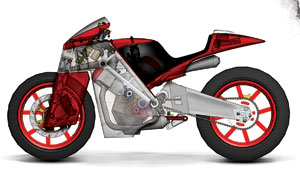

When the leadership for MotoGP decided to replace its 250cc two-stroke class with a four-stroke class called Moto2, Cosentino believed he had found his destiny. He drew a design for a bike that would use his chassis and a custom V4. His racer was intended to compete on a high-visibility international stage, and Cosentino found solid backing for his project.

After months of hard work, the FIM, sanctioning body for MotoGP and Moto2, dealt Cosentino and other independent builders a hard blow when they announced all racers in the class would use the same engine. Custom-built chassis were encouraged, but the spec engine would be an in-line four-cylinder, a configuration that doesn’t work well with Cosentino’s chassis. Honda was granted the contract to supply engines, and Cosentino scrapped the plan to build a Moto2 competitor.

Despite the set back, Cosentino decided to complete his V4 race bike. The chassis design is progressive, competitive and proven. Coupled with a reliable, powerful engine, the race bike that results will be well-balanced and innovative, not to mention a unique, American-built race bike. He has good backing and is moving forward, believing that if he builds it they will come.

The engine will be a 600cc fuel-injected V4. The design intentionally uses common bore sizes, stroke, valve sizes and transmission components so that parts available from high-quality aftermarket suppliers can be used. Fuel injection mapping will be simplified. The output goal is 110 horsepower or so at the rear wheel.

“We need a reliable engine above all,” Cosentino says. “If we have decent power, my chassis has a big advantage, so we will be fine.”

Castings are complete, and the engine should run on the dyno by early summer 2010 and be on the track shortly thereafter. His goal is to get the bike on the track and racing. The bike will be piloted by a variety of professional racers, and Cosentino believes some good results will net him the acclaim necessary to put the bike into limited production.

He also understands the V4 600cc engine will attract attention in ways his original single didn’t. “The bike I have now is a track mule. It’s not sexy,” he says “and it’s a single. As cool as it is and as fast it is, it’s a single — they don’t excite people. V4s do.”

On the website created for the new bike, you can find this message:

“Once complete sometime in 2010, we’ll race wherever the hell we can but rest assured, we’ll race.”

The grit and determination that enabled a nine-year-old Cosentino to build his own go-kart lives on. The V4 engine will run this summer, and race tracks on the eastern seaboard and around the country will be treated to the wail of his hand-built machine at speed.

If you aren’t fortunate enough to see this American original run, you can at least appreciate his spark of hope and determination in times not conducive to either.

More Information

Follow the progress of Chris Cosentino and the Cosomoto motorcycle

You can also follow Cosentino’s blog